In Loving Memory of Memorial

She was once considered among the finest in the nation. Folks from states away marveled at her sleek lines, modern appearance, and gentle grace. The product of broken dreams and goals unmet, she sparkled in the glistening summer sunlight as a proud testimony of sheer will to overcome. Sadly, in just a few short years, nothing but memories and two aging photographs remain.

The winter and early spring of 1947 was a wild time for West Frankfort Cardinals owners Pete Mondino and Charlie Jacobs. With Jacobs’ sights set on setting up the business side of the enterprise, baseball man Mondino saw to the sporting side of the venture. Any minor league professional ballclub needed a stadium, and aside from his duties as general manager in charge of putting the Cards initial roster in order, few tasks were more pressing to Pete than getting the new stadium ready for play.

A vacant lot on West Main Street owned by resident Sam Arsht was tabbed as the site for the new ballpark and negations for purchase were soon under way. On February 8th, 1947, the West Frankfort Baseball and Amusement Corporation purchased the 8.8 acre lot adjacent to Edwards Elementary School for $12,000 and designs for a state-of-the art facility were soon commissioned.

The site, former home of the long since closed West Frankfort Coal Company Mine, or “West Mine” as it was commonly called, required a tremendous amount of work just to be transformed into a safe open space, let alone a suitable playing surface for baseball developed with the planned grandstand, concessions, and other trappings of a then-modern facility. Immediately west of Edwards Elementary School, school children watched the transformation take place as their “Dynamite Hill,” formerly a storage bunker for explosives used during mining later turned “king of the hill” base, was razed by bulldozers.

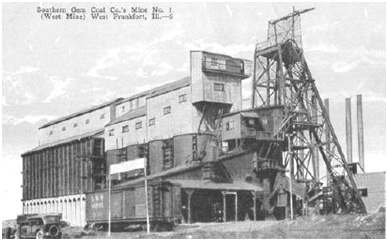

The West Mine had been originally opened in 1912. After a series of closures, stoppages, ownership transfers, and subsequent re-openings, the mine was finally closed for good in 1937. Unfortunately for Mondino and the Cardinals organization, despite its favorable location, the place was an absolute wreck and its deplorable condition made any progress difficult. West had been an old wooden shaft, steam hoist land loading mine, plunging some 470 feet beneath the surface, yet the topside operations were still within the city limits. The mine was initially constructed with a short smokestack, however, townsfolk in homes squatting on adjacent lots complained to mine management so much about the thick black soot which covered their homes depending on how the wind blew that a taller smokestack was constructed. The stack remained long after the mine had closed and to hear former players tell it, even survived after stadium construction as a prominent part of the right field skyline.

- Postcard of the Southern Gem Coal Co. No. 1 Mine (West Mine), circa 1927

Making matters worse, neighborhood residents had begun throwing garbage in the abandoned shaft. Although closed, the mine shaft had not been sealed, making it a poor man’s trash dump and genuine health and safety risk. As is common practice in many mines, the cost to extricate mine machinery lying deep in the bowels of the earth is significantly more than the equipment is worth, making it cheaper to just leave it there. Around 1941, looters had attempted to retrieve some of the abandoned machinery, with an unfortunate underground accident costing one his life. Concerned by the growing threat to public safety, agents of the state permanently sealed the mine in 1942 to prevent anyone from entering again. As in countless other abandoned southern Illinois coal operations, the sealed doors entomb machinery within that remains to this day.

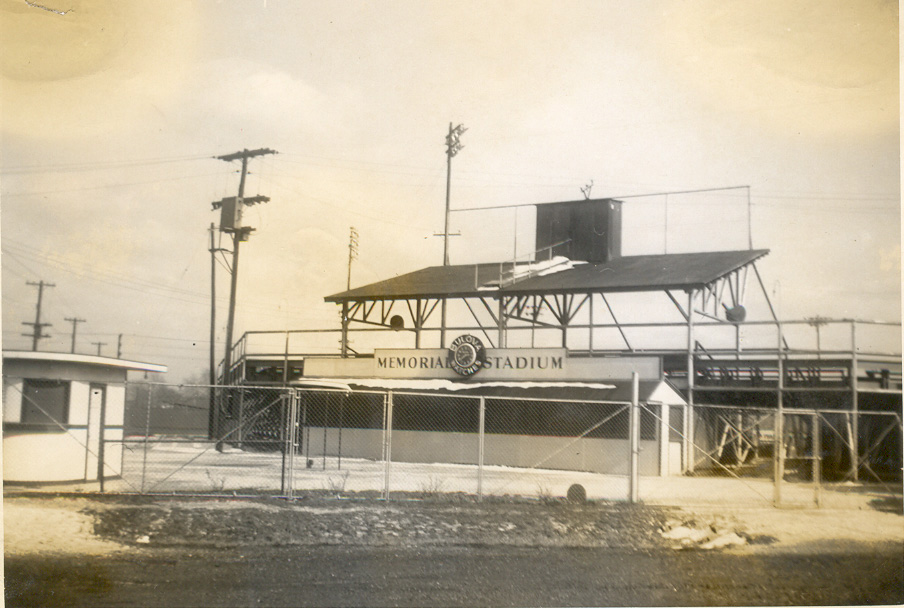

It is unclear exactly who came up with the name, but “Memorial Stadium” was finally coming along. Officials from WFBAC offered a season pass for all 1947 home games to the individual who submitted the name for the stadium that was accepted, however, media outlets never publicized the winning entrant. Battling the clock and Mother Nature, construction crews were unable to get the facility into workable order in time for the home opener originally scheduled for May 20th. That game, already postponed by the league once, was subsequently re-scheduled for Thursday the 22nd, but that too was pushed back until May 24th. Finally, after incessant delays and setbacks, the Cardinals took the field on Saturday, May 24, 1947, exactly 60 years and three days before the Johnny-come-lately Miners would do the same in Marion’s Rent One Park.

Sadly, despite the pomp and circumstance of that May evening, Memorial would be an empty nest after the 1950 season. WFBAC tried to continue to utilize the venue for travelling teams and for local games, but eventually the property was sold to the US government to make way for the National Guard Armory. While rumors persist that home plate from old Memorial Stadium is still out there somewhere floating around as a travelling trophy of sorts, efforts to locate it have failed. To my knowledge, these photos of Memorial, provided by area resident Bob Maragni, are the only proof left that the stadium ever even existed.

- Memorial Stadium. Edwards School is seen to the East (top) and Main Street to the North (right). Photo provided by Bob Maragni

- Memorial Stadium Grandstand. Photo provided by Bob Maragni

So what about you? Do you have any memories of the Cards’ old stomping grounds? Her memory serves as a powerful reminder to cherish the present, for there are no guarantees for tomorrow.

One Comment

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

We grew up hearing stories about the rich history of the coal mine league. There was good reason to be confident in the ability of the area to support a professional minor league team. For decades after world war I, the ever-expanding coal mines had such superior pay compared to agricultural efforts that many athletic and active young men were drawn to seek their fortunes underground. Some sport was inevitably going to be selected for all of these young men to pursue, and baseball was America’s darling, for good reason. Every single coal mining company had a franchise team, many of which were ‘fed’ by a network of team-B, team-C, etc. with dozens of players vying to be chosen for their mine’s competition baseball team to represent the mine in the regional mining league. Southern Illinois mining league teams were regularly scouted for talent, and it would be interesting to discover how many professional players of that golden age of radio and Babe Ruth may have come out of this area.

Hand-me-down stories include tales of ‘the negro team’ from one mine doing very well, though they were not allowed to play on the same team with the rest.

One tale I know that did not come to fruition was that of Leo Sanders of Fudgetown (Ferges). Local hero at some point in the 20’s, he was the catcher and home-run king around the era, either during or possibly shortly after, when people were hearing broadcasts and had been lionizing the accomplishments of the legendary Ruth.

Sanders was scouted and recruited to become the ‘next star’ catcher of the Chicago Cubs, expected to bolster their crew of sluggers. Unfortunately, however, not only did players not receive the kind of generosity expected of instant-millions these days, but his young wife apparently announced an addition to their family on the way. He declined his chance to become part of professional baseball history to stay home and take care of his new family, between mining and farming their little piece of Williamson County. Who knows – had a bonus check been part of the deal in those days, we might have had the chance to reminisce about the legendary home runs of local Cubs slugger Leo Sanders. Such possibilities are now relegated to the fading memories of those passing down the stories of the farm teams that built the local passion for baseball which led to the West Frankfort Cardinals.